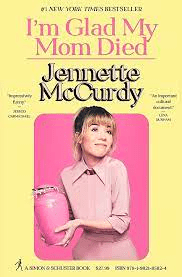

This memoir, with its shocking title, was an irresistible read. Jennette McCurdy, a child star on iCarly, a 1990’s Nickelodeon hit, reveals her lived experience growing up with her mom, Debra McCurdy. From her earliest memory, Jennette learned that pleasing her mother would bring approval, peace and possibly even love – so this became her constant obsession. Whenever Jennette had her own thoughts or preferences, she would find that it was easier to suppress those and just go along with whatever her mother’s preferences were, even when it meant her doing the things she hated – including acting!

As shocking as the title is, so, too, are many of the details of Jennette’s life. So as not to give too much away, I will hold back on these, but suffice it to say, her mom was a narcissist, a hoarder, a pathological liar, and an abusive wife and mother. Nevertheless, this story is told with an admirable dose of humor, humility, and compassion, even when resentment and anger would be entirely justified. Jennette pays a heavy mental health toll for her upbringing and I am hopeful that writing this book was cathartic and therapeutic for her. I have to imagine it was.

One of the consequences for her that I will reveal – skip this paragraph if you plan to read it and don’t want to know anything about her before you do – is that she developed an eating disorder. In fact, at age 11, her mother actually instructed her in exactly HOW to have an eating disorder, which is more the point. They co-restricted, rejoiced together in how little they ate, almost competing in how few calories they might consume in a day, and monitored Jennette’s weight together as a mutual obsession. Her weight became a measure of how “good” she was, in every way possible. And this is how she learned to define herself, her weight truly defined her.

If you’ve read any of my other entries in this blog, you’ll know that this is not the usual genre that I read. I do not generally read about TV or pop stars. But this memoir had its own merits, not because of how famous Jennette is but more because of what she endured and what she fought to overcome. She is an admirable young woman and I hope that she continues to fight the good fight. I hope she succeeds in finding who she is underneath it all.