Grace is on the brink and she doesn’t know where to turn. She knows she can’t be trusted with the care of her own children – she just can’t pull her mind out from under the dense blackness that has taken root there, and she knows that it’ll happen again if she has another child. It’s happened each time before. She just has nowhere to turn.

Decades later, Beth is grappling with her own frustration. She is clearly just stressed – her father is dying, she’s sleep deprived from a new baby, and she’s just not feeling up to going back to work yet. So why is everyone on her case, asking her what’s wrong? She’ll be fine. Won’t she?

The narrative between these two women brings us back and forth through the generations of this vulnerable, tender family and winds us through a beautiful story of love, heartbreak, and resilience.

The difference between these two women is also just one generation, and the epic difference between their generations is the passing of Roe v. Wade. One generation has the luxury of choice – the other lives without any control because they do not have that access.

I find myself writing this post on the morning that the Supreme Court of the US, staggeringly, has announced the repeal of Roe. I am still numb from this, even having tried to brace myself for what I knew was coming, although I still held out hope that some of the judges would come out on the just side of history. But no, the 6 conservative judges’ allegiance to their biased, misogynistic, utterly anti-life, hypocritical base was clearly too strong a tie.

Women will now return to the back alleys, the sepsis-inducing, life-threatening, desperate means of trying to gain control of their lives, which men put them at risk of, once again. Women will have to endure pregnancies they do not want, bear children they’re not ready to care for, and those children will likely live in conditions that are sub-par, to say the least, because those same Conservatives never vote for safeguards for these children once they are born. Hypocrisy at its very gravest.

Health care should be left to health care providers and their patients. Everyone else should stay out of it. Abortion and contraception is health care. Period.

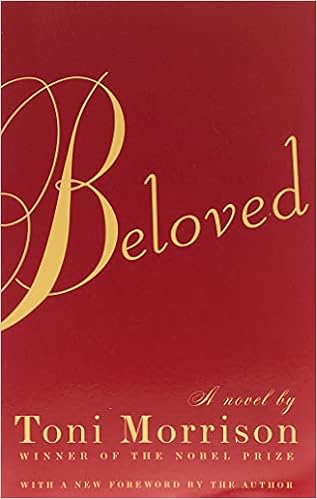

This is a MUST READ at this time – I really wish the SCOTUS judges had read this novel before writing this decision.